A bold move is afoot in the House of Representatives to return Nigeria to a parliamentary system of government. Will the constitutional amendment bill become a law? Here’s what you need to know

Nigeria’s political landscape might be on the brink of a transformative shift with the introduction of a constitution amendment bill sponsored by the House of Representatives Minority Leader, Rep. Kingsley Chinda and 59 others has passed second reading.

The bill proposes a radical restructuring of the executive branch, establishing a Prime Minister as Head of Government and redesignating the President as Head of State and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.

For students of Nigerian history, this dual-leadership model echoes the parliamentary system of the First Republic (1960–1966).

Yet, the 2025 proposal is no mere historical trip, it blends past lessons with a modern twist. As Nigeria contemplates this change, a look back at its history, alongside the potential benefits and pitfalls offers insight into what lies ahead.

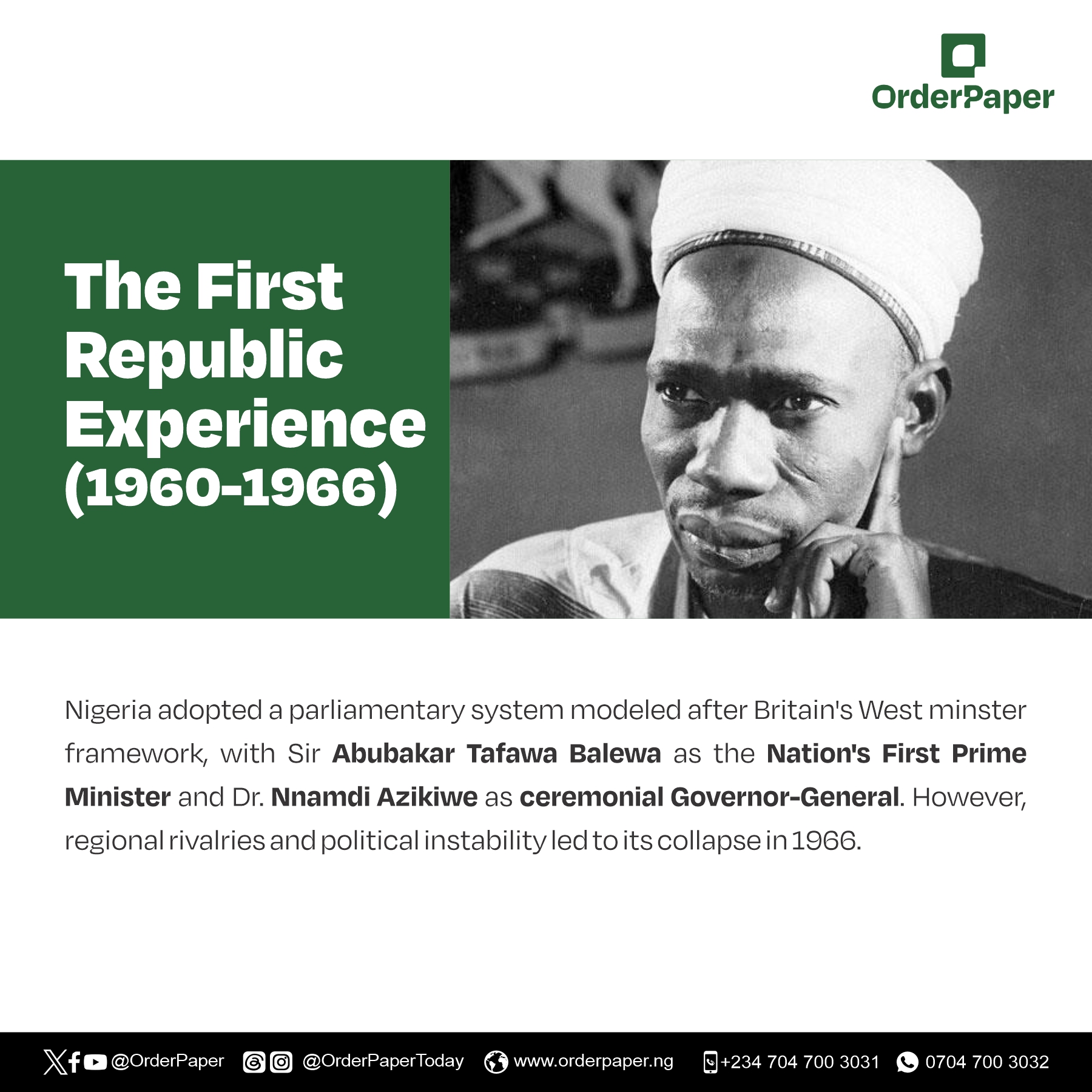

Parliamentary Past: The First Republic Experience

When Nigeria gained independence in 1960, it adopted a parliamentary system modeled after Britain’s Westminster framework. Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, the nation’s first Prime Minister, led the government from the House of Representatives, while Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe served as a ceremonial Governor-General (and later President after 1963).

The Prime Minister wielded executive power, relying on parliamentary support, while the Head of State symbolized national unity. This system aimed to foster legislative accountability and regional representation in a newly independent, multi-ethnic nation.

However, the First Republic’s parliamentary experiment crumbled by 1966. Regional rivalries, political instability, and electoral disputes resulting in the controversial 1964–1965 elections exposed which its fragility.

The military coup of January 1966 ended this era, paving the way for decades of military rule and the eventual adoption of a presidential system in 1979.

While some might argue that the parliamentary model failed to manage Nigeria’s diversity, some might point to poor implementation rather than inherent flaws.

READ ALSO: Proposed prime minister bill is a needless distraction

The 2025 Parliamentary Proposal: A Hybrid Revival

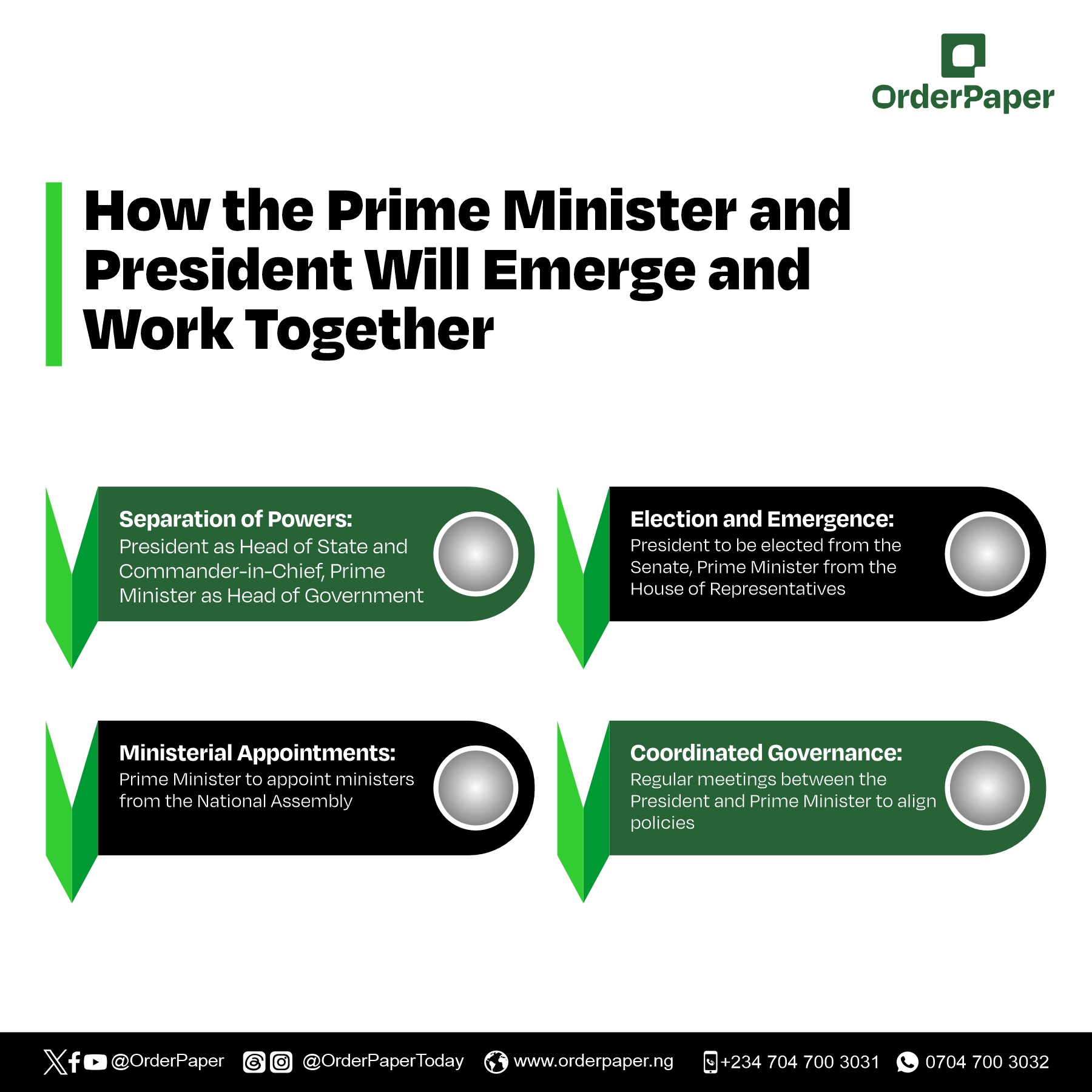

Fast forward to 2025, and the bill seeks to resurrect elements of this parliamentary past, although with adaptations. Unlike the First Republic, where the Head of State was largely ceremonial, the new bill assigns the President substantive roles, including command of the armed forces, while the Prime Minister takes charge of day-to-day governance.

Both leaders would be elected from within the National Assembly with the President from the Senate while the Prime Minister, from the House of Representatives tying executive power directly to the legislature.

The bill also outlines a detailed election process, requiring nominations from fellow lawmakers and secret ballots to ensure a democratic selection. Ministers, appointed by the Prime Minister from the National Assembly, would work under a coordinated framework involving regular meetings with the President to align policies.

This hybrid model departs from the centralized authority of Nigeria’s current presidential system, aiming to distribute power and enhance legislative oversight.

Parliamentary Govt from other Climes

The United Kingdom’s parliamentary system is a shining example of success, with Prime Minister Keir Starmer governing with cabinet support while King Charles III remains above politics as Head of State.

A notable demonstration of this system’s flexibility was the seamless transition from Boris Johnson to Liz Truss in 2022, showcasing parliament’s ability to adapt leadership without destabilizing the state. This is a valuable lesson for Nigeria as it considers a similar parliamentary system.

India’s parliamentary model, adopted post-independence, is another noteworthy example. With a ceremonial President and a powerful Prime Minister, India has achieved a balance of power. Narendra Modi’s tenure since 2014 illustrates how a strong Prime Minister can drive policy, while President Droupadi Murmu focuses on constitutional duties.

India’s system has thrived by balancing regional diversity, a challenge that Nigeria also faces, making it a valuable case study for Nigeria’s parliamentary aspirations.

Pros and Cons of the New Proposal

Proponents of the House bill argue that Nigeria’s presidential system has significant drawbacks, including the concentration of power in one office, leading to inefficiency and unaccountability. To address this, the proposed system would separate the Head of State from the Head of Government, preventing the over-centralization of power. This would allow the President to act as a stabilizing figure while the Prime Minister manages executive duties, promoting checks and balances.

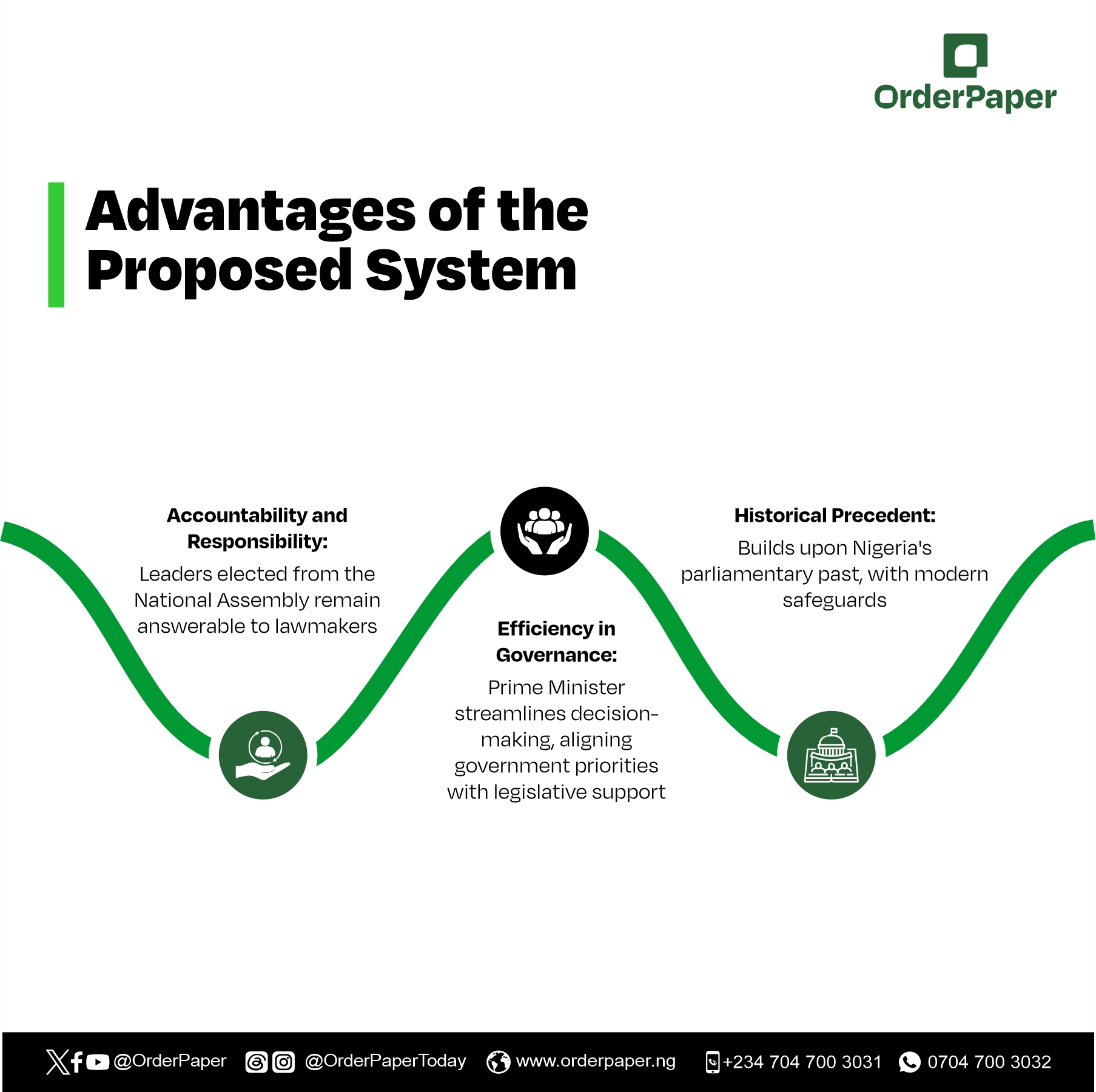

The proposed system also offers several advantages, including legislative accountability, efficiency in governance, and historical precedent. By electing leaders from the National Assembly, they would remain answerable to lawmakers, reducing executive overreach and fostering collaboration.

The Prime Minister, as a parliamentarian, could streamline decision-making by aligning government priorities with legislative support. Additionally, Nigeria’s parliamentary past, despite its collapse, showed moments of promise, offering a foundation to build upon with modern safeguards.

However, there are also risks and challenges associated with this shift. These include power ambiguity, exclusionary candidacy, echoes of instability, and implementation hurdles. Dividing roles between the President and Prime Minister could lead to confusion or rivalry, while limiting eligibility to National Assembly members could exclude other qualified Nigerians.

The First Republic’s collapse also raises questions about whether a parliamentary-style system can withstand Nigeria’s complex socio-political dynamics. Furthermore, transitioning from a presidential to a hybrid system requires meticulous execution to avoid deepening public skepticism about governance reforms.

A Path Forward?

If this new proposal is to succeed, it must address these historical pitfalls—perhaps by clarifying roles, broadening participation, and ensuring robust mechanisms to manage conflict.

As Nigeria stands at this crossroads, the bill invites debate: Can a hybrid model balance the strengths of its past with the demands of its present?

The answer lies not just in the text of the constitution but in the will to implement it effectively. For a nation long wrestling with governance challenges, this could be a contemplation toward renewal or a revisit of old ghosts. Only time, and the Nigerian people, will tell.