Non-compliance with legislative summons and resolutions is a key factor responsible for declining public accountability by government ministries, deparments and agencies

Rarely does a week pass by at the National Assembly without reports of government ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) disregarding summons from Senate and House of Representatives committees.

Legislative summons and the law

To some observers of the national assembly, this trend of non-compliance suggests that lawmakers or committees lack the legal authority to issue summons. Some even go to the extent of referring to the legislative body as a “toothless bulldog” that only barks but cannot bite. But what does the law and statutes say?

The 1999 constitution (as amended) in section 88 states that, “Each House of the National Assembly shall have power by resolution published in its journal or in the official gazette of the Government of the Federation to direct or cause to be directed an investigation into – a) any matter or thing with respect to which it has power to make laws; and b) the conduct of affairs of any person, authority, ministry or government department charged, or intended to be charged, with the duty of or responsibility for – I. executing or administering laws enacted by the National Assembly, and II. disbursing or administering moneys appropriated or to be appropriated by the National Assembly,”

ALSO READ: 5 failed motions in 6 months of 10th Reps | MOTIONS & MOVEMENT

To perhaps strengthen the above, section 89 (c) of the same constitution empowers the National Assembly to “summon any person in Nigeria to give evidence at any place or produce any document or other thing in his possession or under his control, and examine him as a witness and require him to produce any document or other thing in his possession or under his control, subject to all just exceptions”

Also sections 4, 5, 6 of the Legislative Houses (Powers and Privileges) Act, 2017 empowers legislative houses to summon individuals to appear and provide evidence, and if a person fails to attend after a summons, the president of the senate or speaker of the house can issue a warrant for their arrest.

Is the national assembly a toothless bulldog?

While the constitution and the legislative powers and privileges act are clear on power to summon, they have not provided a clear position on what happens in cases of default, whether occasional or persistent. Even when a warrant of arrest as been issued, there are still cases of non-compliance. Section 89(d) of the 1999 constitution (as amended) states that “A warrant is issued to compel the attendance of any person who, after having been summoned to attend, fails, refuses or neglects to do so and does not excuse such failure, refusal or neglect to the satisfaction of the House or the committee in question,”

In instances where such warrants do not see the light of the day, as is often the case, the section only mandates the national assembly to “order him (the person summoned) to pay all costs which may have been occasioned” in the course of issuing the summons and “any fine so imposed shall be recoverable in the same manner as a fine imposed by a court of law.”

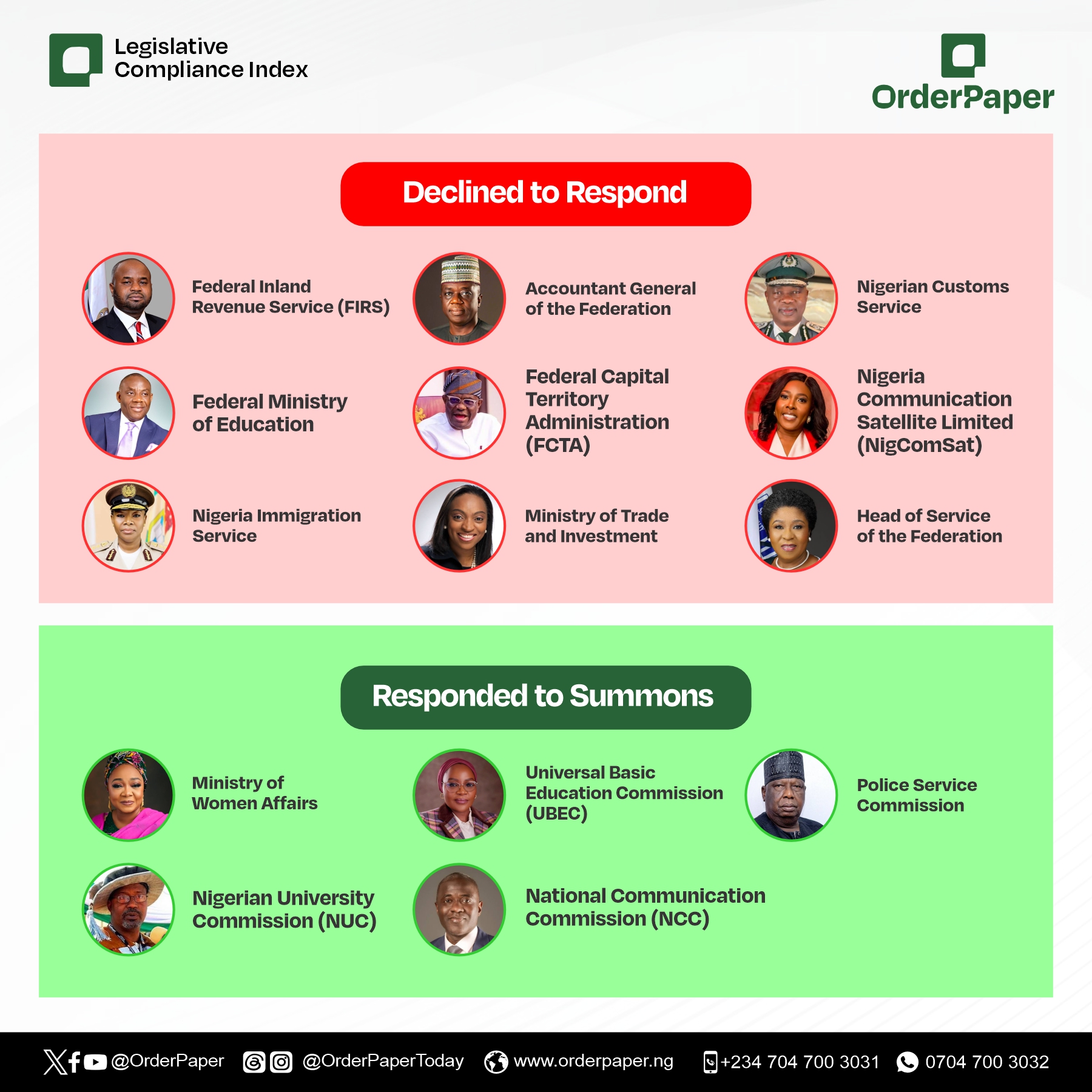

Culprits: FIRS, Customs, NigComSat, etc

It is not news that the National Assembly has continued to grapple with how some heads of MDAs repeatedly refuse to comply with summons by its committees.

Parliament Reports recently reported how the House Committee on Legislative Compliance summoned thirteen MDAs to appear before the committee on February 6, 2025 or face sanctions.

However, as at time of filing this report, nine of these agencies are yet to comply with the legislative summons despite threats of sanctions.

Leading among these agencies which continued to play defiance are the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS), Nigerian Custom Service, Accountant General of the Federation and Federal Ministry of Education.

Others are Federal Capital Territory Administration (FCTA), Nigeria Communication Satellite Limited (NigComSat), Nigeria Immigration Service, Ministry of Trade and Investment, and the Head of Service of the Federation.

Parliament Reports made several unsuccessful attempts to get responses from these MDAs for this story.

While several agencies ignored the summons, some complied with the invitation and engaged with the committee. They are: Ministry of Women Affairs, Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC), Police Service Commission, Nigerian University Commission (NUC), National Communication Commission (NCC).

Threats of sanctions rescinded?

In a related development, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of the House, had during 2025 budget defence exercise, recommended the exclusion of the National Examination Council (NECO), University of Ibadan (UI), Federal Ministry of Labour and Employment, and 21 other MDAs and institutions from the 2025 appropriation over their refusal to appear before the committee.

It is not clear why the national assembly still appropriated funds for these MDAs in spite of the recommendation.

Expectedly, such conduct by the national assembly itself tends to embolden the continued refusal of public agencies to appear before parliament. At the end, this situation raises serious concerns about accountability and transparency in governance which lawmakers have a primary responsibility to promote.

Legal perspective

Renown civic activist, legal expert and President of the Public Interest Lawyers League (PILL), Dr. Abdul Mahmud, weighed in on the issue in an interview with Parliament Reports. He posited that the summons issued by the national assembly carry constitutional validity, yet they are frequently ignored due to institutional weaknesses and executive interference.

Speaking on the persistent refusal of MDAs to honor legislative invitations, Mahmud highlighted several key factors responsible for this trend.

He said: “The national assembly itself, an assembly that pampers the executive branch, an assembly that has become the rubber stamp of the executive branch, the tendency exists that MDAs of the executive branch would not show constitutional respect, as one expects, to the national assembly.

“But one important thing I also have to stress is the attitude of the executive in politically shielding its executives from attending or heeding summons of the national assembly. And more importantly too, the inability of the national assembly to wield its big stick when chief executives of MDAs refuse to appear before it is a serious problem which I think the national assembly must address.”

He emphasised that “the summons issued by the national assembly are not like ordinary summons from the police or administrative bodies. These are constitutional summons, backed by the force of the constitution.”

Citing the Supreme Court ruling in Tony Momoh v. National Assembly (1982-1983), Mahmud emphasised that the legislature’s authority is constitutionally grounded. Sections 88(c) and 89(d) of the 1999 constitution empower the national assembly to issue arrest warrants against officials who fail to appear. However, he noted that weak enforcement mechanisms have rendered these provisions ineffective.

To address this challenge, Mahmud suggested several reform measures, including: stronger penalties for defaulters, such as automatic suspension, budgetary sanctions, and career blacklisting.

He reiterated that “strengthening legal enforcement mechanisms and ensuring law enforcement agencies act on arrest warrants promptly would enhance compliance,” adding that if the national assembly enforces its powers effectively, it can restore its authority and ensure greater accountability from MDAs.

Abonta identifies key challenges

Rep. Uzoma Nkem Abonta, a former fourth-term lawmaker who represented the Ukwa East and Ukwa West federal constituency of Abia state in the House of Representatives, explained that the constitution grants the legislature broad oversight powers, including the authority to demand documents, summon officials, and even issue arrest warrants when MDAs refuse to comply.

He attributes the failure to enforce legislative summons to a combination of legislative slack, lack of political will, enforcement gaps, political interference, and capacity deficits among lawmakers.

He said: “I think the reason for not answering them (summons ) may be what I would describe as legislative slack. If legislators really mean to bring such persons, MDA’s to do what is required, they will do so.

“Legislators can use the power of the purse. If an MDA refuses to clear queries on previous budgets, why should they be allowed to present a new one? But when legislators lack the will to enforce compliance, MDAs take advantage,” he explained.

He also noted that legislative summons and legislative invitations differ, with the former carrying the force of law. However, lawmakers often fail to follow due process in issuing valid summons, leading to non-compliance by MDAs.

“Mind you, legislative invitations are different from legislative summons. If you go through the procedure and issue a legislative summons, they will answer it as if they were answering a court summons. They will appear.

“During my time in the public petitions committee, we used it a lot to secure the attendance of some ministers or highly placed. We tried to arrest and did in fact issue a proper summons. And they showed up to say or produce what we wanted them to do,” Rep. Abonta added.

Beyond legislative slack, party politics plays a major role in shielding MDAs from scrutiny, he also said. Abonta noted that when a committee chairman from one party summons an official appointed by the ruling party, political interference often blocks accountability efforts.

“Another compelling, very compelling factor contributing to the defense of MDAs is just party sentiment and politics. Should a chairman from party A summon a minister or MDA, the party B, perhaps being the party in power, may begin to see it as trying to expose inefficiency or corruption, or as the case may be, they’ll begin to apply a lot of calls, what I may call long legs, or reach tall orders to say, no, don’t do this, you know, this will do this. So party sentiments and party politics interfere a lot.

“They begin to say, you know, we can’t do this, give him a safe landing or this. Before you know it, it will become members against members. The members depend on who has the MDA and how he lobbies his things and so on.

“You will see parliament will get divided to say, no, we can’t do this now, we’ll see him privately, we’ll come and see him. For crying out loud, party interference, political interference, so to say, is the strongest factor for disobedience of parliament or parliamentary summons,” he explained.

He cited past instances where party influence delayed or weakened legislative investigations, even though some ministers—like Rotimi Amaechi and Godswill Akpabio as Minister of Niger Delta Affairs—eventually complied with summons.

“During Buhari’s tenure, he ordered all ministers to answer parliamentary summons. It worked to some extent, but without that directive, party interference often prevails,” he noted.

Another major challenge highlighted by Rep. Abonta is the lack of training and expertise among lawmakers in conducting effective legislative oversight. Many legislators come from diverse professional backgrounds and lack investigative and adjudication skills, leading to procedural errors that undermine the validity of their summons.

“Capacity and experience is also very responsible for non-implementation of securing the presence of MDAs. Legislators need to be trained, they need to be trained in the act of doing this assignment.

“Capacity, most of the legislators are from various walks of life and are not trained in the act of adjudication, investigation, and inquiry. It requires special acts, techniques, expertise to do inquiry.

“So the manner of couching your invitation, your summons, and reason for summoning, at times people who are not connected or persons who are not connected are being summoned. I mean, a bad order is as good as not being obeyed,” Rep. Abonta stated.

Civil society shares perspective…

A civil society actor, Botti Isaac, who is Programme Coordinator for Social Action, raised concerns about the scope and limitations of the legislature’s oversight functions.

According to him, while the national assembly has the constitutional authority to investigate and summon persons for inquiry, this power is not absolute. “Yes, they have the power, but it is limited to two key functions: legislating a law and exposing corruption,” he explained.

He cited Section 88(2) of the constitution, which specifies that the national assembly can only summon individuals or agencies for:

Legislative Purposes – Lawmakers can request documents, testimonies, or evidence needed for drafting, amending, or reviewing laws.

Exposing Corruption – If a public official or organization is suspected of mismanaging public funds or engaging in corrupt activities within the scope of legislative oversight.

However, Isaac emphasized that the legislature’s power does not extend to enforcement actions such as arrests or prosecution. “The national assembly cannot prosecute or arrest individuals. Their duty is only to expose corruption. It is the executive’s role, through agencies like the EFCC, ICPC, or NFIU, to investigate further and prosecute offenders,” he noted.

He further explained why some MDAs often refuse to comply with legislative summons. “If a matter is outside the scope of legislative functions, the MDAs are not obligated to respond. The law is clear that their power is limited to oversight functions directly tied to legislation and corruption exposure,” he said.

“If an investigation does not serve the purpose of lawmaking or corruption exposure, agencies will simply disregard it. That is why many ignore certain invitations,” he added.

Accountability is being arrested

With recent legislative probes into road infrastructure funding, petroleum levies, and other government expenditures, Isaac urged the National Assembly to ensure that its investigations align with constitutional provisions. He also called on lawmakers to refer cases of corruption to the appropriate executive bodies for further action.

“The constitution is not ambiguous. The national assembly must operate within its defined powers and avoid overreaching its authority. Otherwise, its summons will continue to face resistance from agencies and individuals,” he concluded.

LEGISLATIVE COMPLIANCE INDEX (LCI): This is a governance accountability tool designed by OrderPaper Nigeria to assess the responsiveness or otherwise of public and private sector stakeholders, including MDAs, to legislative summons and resolutions stemming from both Houses of the National Assembly.