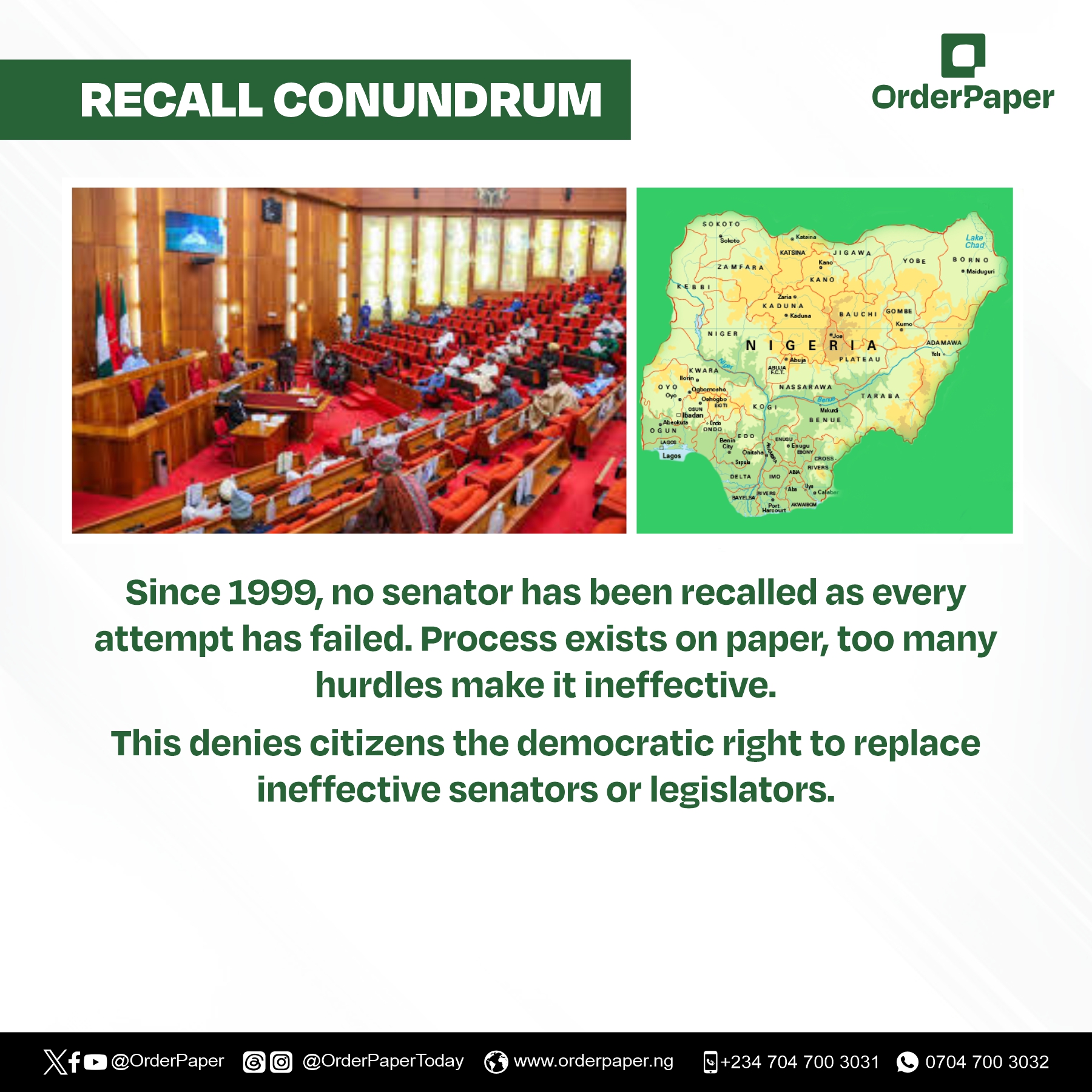

Since 1999, no lawmaker has been sacked by citizens during their tenure, exposing the recall process as an impotent safeguard against poor representation

When Nigeria transitioned to democracy in 1999 after years of military rule, its constitution provided a mechanism that allowed citizens to hold their elected representatives accountable. Among these mechanisms was the power of recall, a constitutional process that gives constituents the right to remove a lawmaker before the end of their tenure if they are dissatisfied with their performance.

However, over two decades later, this power remains nothing more than an illusion. No lawmaker has ever been successfully recalled in Nigeria’s democratic history, whether at the senate, house of representatives or state assembly. Despite multiple attempts, some driven by genuine public dissatisfaction, others by political rivalries, none has resulted in the removal of a lawmaker through the formal recall process.

Recall vs. Suspension: Discipline or Vendetta?

It is crucial to differentiate between a recall and a suspension of an incumbent lawmaker.

•Recall: A recall is initiated by constituents who seek to remove an elected official before the end of their term. It requires a petition signed by more than 50 percent of registered voters in the affected constituency. If the petition meets constitutional requirements, a referendum is held where the majority vote determines whether the lawmaker remains or is removed.

READ ALSO: Senate Suspensions: A look back since 1999

•Suspension: Unlike a recall, a suspension is an internal disciplinary measure imposed by the legislative body. It temporarily removes a member from their duties due to alleged misconduct or breaches of legislative rules.

Section 69 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended) says, “A member of the Senate or of the House of Representatives may be recalled as such a member if:

(a) there is presented to the Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission a petition in that behalf signed by more than one-half of the persons registered to vote in that member’s constituency alleging their loss of confidence in that member; and

(b) the petition is thereafter, in a referendum conducted by the Independent National Electoral Commission within ninety days of the date of the receipt of the petition, approved by a simple majority of the votes of the persons registered to vote in that member’s constituency.”

Interestingly, while multiple lawmakers have been suspended at various points since 1999, no lawmaker has ever been successfully recalled by their constituents.

In the House of Representatives, there have been attempts to recall members but all failed. Some of them who are now former members include, Architect George Ike Okoye (Anambra – 1999), Farouk Adamu (Jigawa – 2006) and Abdulmumin Jibrin Kofa (Kano – 2017).

Sen. Natasha Dodges the ‘Recall’ Bullet

The latest in this line of failed recall efforts is the move against Sen. Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan (PDP, Kogi Central) in the extant 10th senate.

In March 2025, a petition calling for her recall was submitted to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). The petitioners, who claimed to have secured over 250,000 signatures from registered voters in Kogi central, cited a “loss of confidence” in her leadership. However, in April 2025, INEC rejected the petition, stating that it did not meet the constitutional requirements for a recall.

Sen. Akpoti-Uduaghan, who is currently suspended from the senate over allegations of violating legislative rules, described the recall attempt as politically motivated. She accused INEC of bias, alleging that the commission had actively guided the petitioners on how to correct deficiencies in their submission.

At her homecoming rally, she described the recall attempt as perceived inconsistency in the electoral body’s handling of the process.

This latest recall attempt has once again exposed the weaknesses in Nigeria’s recall system, which, despite being enshrined in the constitution, has never successfully removed a lawmaker from office.

Other failed recall attempts since 1999

Sen. Ibrahim Mantu (Plateau central, 2005) –

In December 2005, a recall petition against late Sen. Ibrahim Mantu, the then Deputy Senate President, was spearheaded by Capt. Joseph Din, a political rival. The petition reportedly secured 280,408 signatures out of 388,833 registered voters, surpassing the constitutional threshold. However, the recall process stalled when Mantu challenged it in court, alleging forgery and procedural irregularities. The legal battles and political interference ensured that the process never reached the referendum stage.

Simon Bako Lalong (Plateau Assembly Speaker, 2005)

Before he became governor and incumbent member of the 10th senate, Simon Lalong, then Speaker of the Plateau State House of Assembly, faced a recall petition reportedly signed by over 50,000 voters. However, INEC proceeded with the recall process without giving him access to the petition, leading to legal disputes. Allegations of forged signatures and procedural violations ultimately rendered the recall attempt unsuccessful.

Sen. Chris Ngige (Anambra central, 2012)

In 2012 that some constituents in Anambra central attempted to recall Sen. Chris Ngige. However, the effort collapsed amid allegations of intimidation and coercion. It was claimed that many signatories were forced to withdraw their support under pressure, leading to the recall process dying before it could take off.

Sen. Ali Ndume (Borno south, 2016)

In 2016, a group of constituents from Borno south attempted to recall Sen. Ali Ndume, citing poor representation and a disconnect from the grassroots. However, the recall bid never gained traction beyond the petition stage, as Ndume’s political allies within the state worked to suppress the move. The effort eventually fizzled out without any formal verification by INEC.

Sen. Dino Melaye (Kogi west, 2017)

One of the most high-profile recall attempts in Nigeria’s history was the move against Sen. Dino Melaye in 2017. Melaye, known for his controversial political style, faced backlash from his constituents, who accused him of poor representation and erratic behaviour.

The recall effort was largely influenced by political forces, with the Kogi state government playing an active role in mobilising against him. Despite INEC verifying over 188,000 signatures, the process ultimately collapsed due to legal delays and allegations of forgery. The signature verification exercise recorded a turnout of just 5.3 percent, far below the threshold required for a successful recall. The entire process became a political spectacle rather than a reflection of genuine voter sentiment.

Sen. Bukola Saraki (Kwara central, 2018 – Threatened recall)

While not formally initiated, the former Senate President, Bukola Saraki, was threatened with recall by a group called the Kwara Youth Stakeholders Forum in 2018. The threat emerged during a period of political conflicts between the senate and the presidency, but it never materialised into an actual petition.

Why has no lawmaker been recalled?

The repeated failures of recall attempts in Nigeria highlight deep flaws in the system:

1.Legal and procedural hurdles: The recall process is deliberately complex, requiring over 50 percent of registered voters to sign a petition before a referendum can even be scheduled. Given voter apathy and the difficulty in mobilising such numbers, most recall attempts fail at this stage.

2.Political interference: Recall efforts often become political battles rather than genuine expressions of constituents’ dissatisfaction. Powerful politicians use their influence to suppress recall efforts, while opposing factions exploit the process for political gain.

3.Allegations of forgery and coercion: In many cases, recall petitions have been tainted by allegations of forged signatures or intimidation, leading to legal challenges that stall the process indefinitely.

4.Administrive challenge: The electoral body has often been accused of inconsistencies in handling recall petitions. While it claims to follow due process, its role in some cases such as the recent Akpoti-Uduaghan recall attempt, raises questions about possible external influence.

The future of recall in Nigeria

The recall mechanism, as currently designed, appears almost impossible to execute successfully. While it was introduced as a tool for accountability, it has instead become a political weapon used more for intimidation than actual democratic governance.

For now, Sen. Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan joins the long list of senators whose recall efforts have collapsed under the weight of Nigeria’s flawed electoral system. Her case, like those before her, serves as yet another reminder that in Nigeria’s democracy, the power of the people to remove their representatives remains largely theoretical.