The Natasha-Akpabio brouhaha brings to the fore the low representation of women in the national and state assemblies of Nigeria

![]()

Breaking Barriers

The conversation around gender equality in governance has again taken center stage. Recently, the Deputy Speaker of the House of Representatives, Rep. Benjamin Okezie Kalu (APC, Abia), renewed calls for legislative reforms to enhance women’s representation in Nigeria’s political landscape. He spoke at a three-day workshop on the operational guidelines for the national women leaders forum, highlighting the push for reserved seats for women.

Rep. Kalu and 12 other members of the House sponsored a bill that proposed the creation of one additional legislative seat to be contested by women only for each state and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) in the Senate and House of Representatives, which would total 74 seats. The bill also proposed three special seats for women at each of the 36 State Houses of Assembly totalling 108 women only seats at the sub-national level. The bill passed second reading in July 2024 and was referred to the committee on constitution review for further legislative action.

History of the special seats bill

In the 9th Assembly, Rep. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha, alongside 85 co-sponsors, including former Speaker Femi Gbajabiamila first introduced this bill. It was part of the five proposed gender bills aimed at addressing women’s representation in the constitutional amendment process. However, it failed to pass during the voting session in March 2022.

Initially, the bill proposed 111 special seats for women in the federal legislature—three per state and one for the FCT across the Senate and House of Representatives. However, this current version of the bill reduced this to 74 seats to address concerns about an expanded legislature.

A Glaring Gender Gap

The bill seeks to address the under-representation of women in Nigeria’s legislature, where the 10th assembly has only 4 out of 109 senators and 16 out of 360 representatives are women.

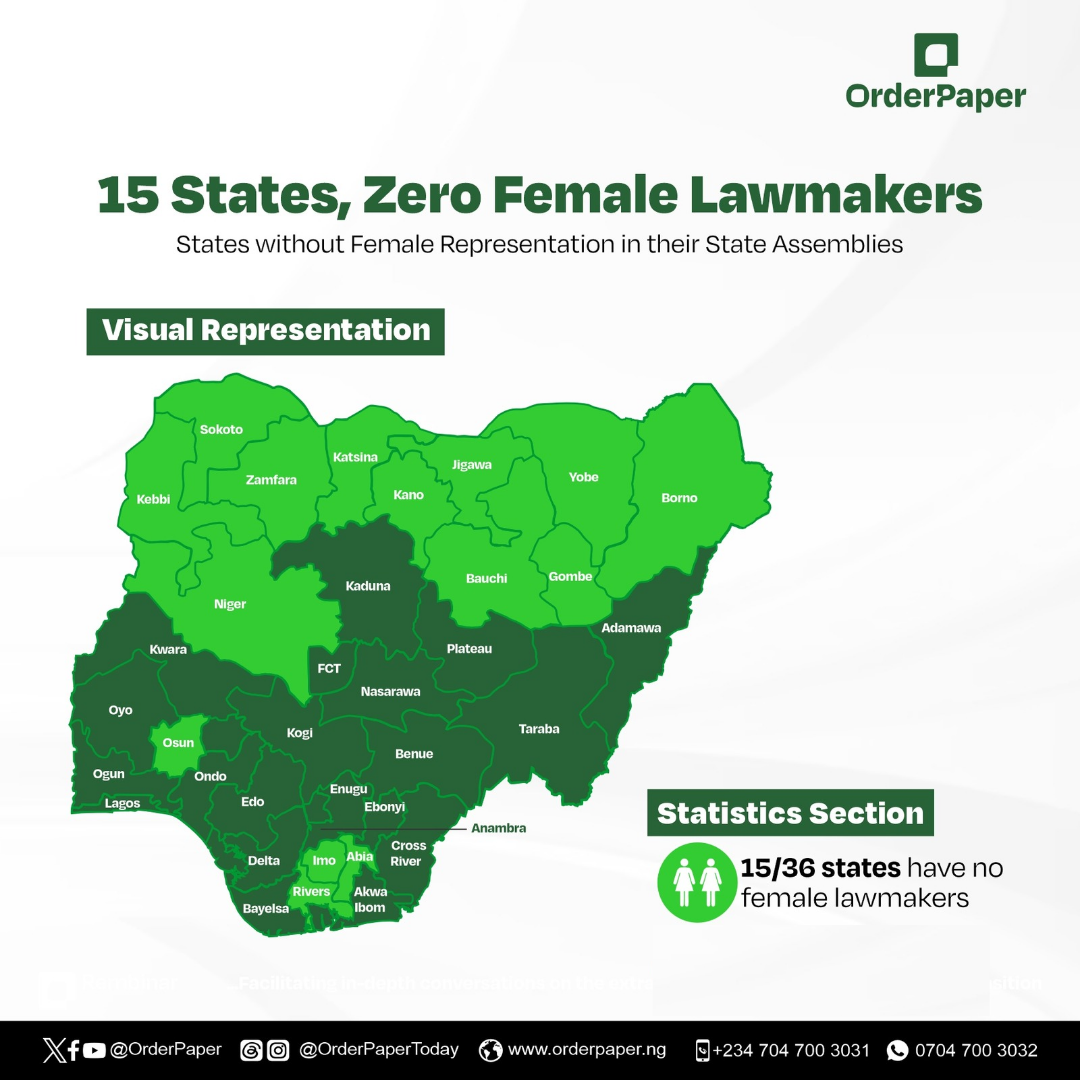

Also, 15 states in Nigeria lack a single female lawmaker. These are Abia, Rivers, Zamfara, Kano, Osun, Imo, Yobe, Bauchi, Niger, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kebbi, Katsina and Sokoto. This paints a bleak picture of gender imbalance in the country’s legislative framework.

Beyond the numbers, this gender gap has real-life consequences. It means that women, who constitute nearly half of Nigeria’s population, have limited influence on policies that affect their lives, from healthcare and education to economic empowerment and security.

Lessons from other African Countries

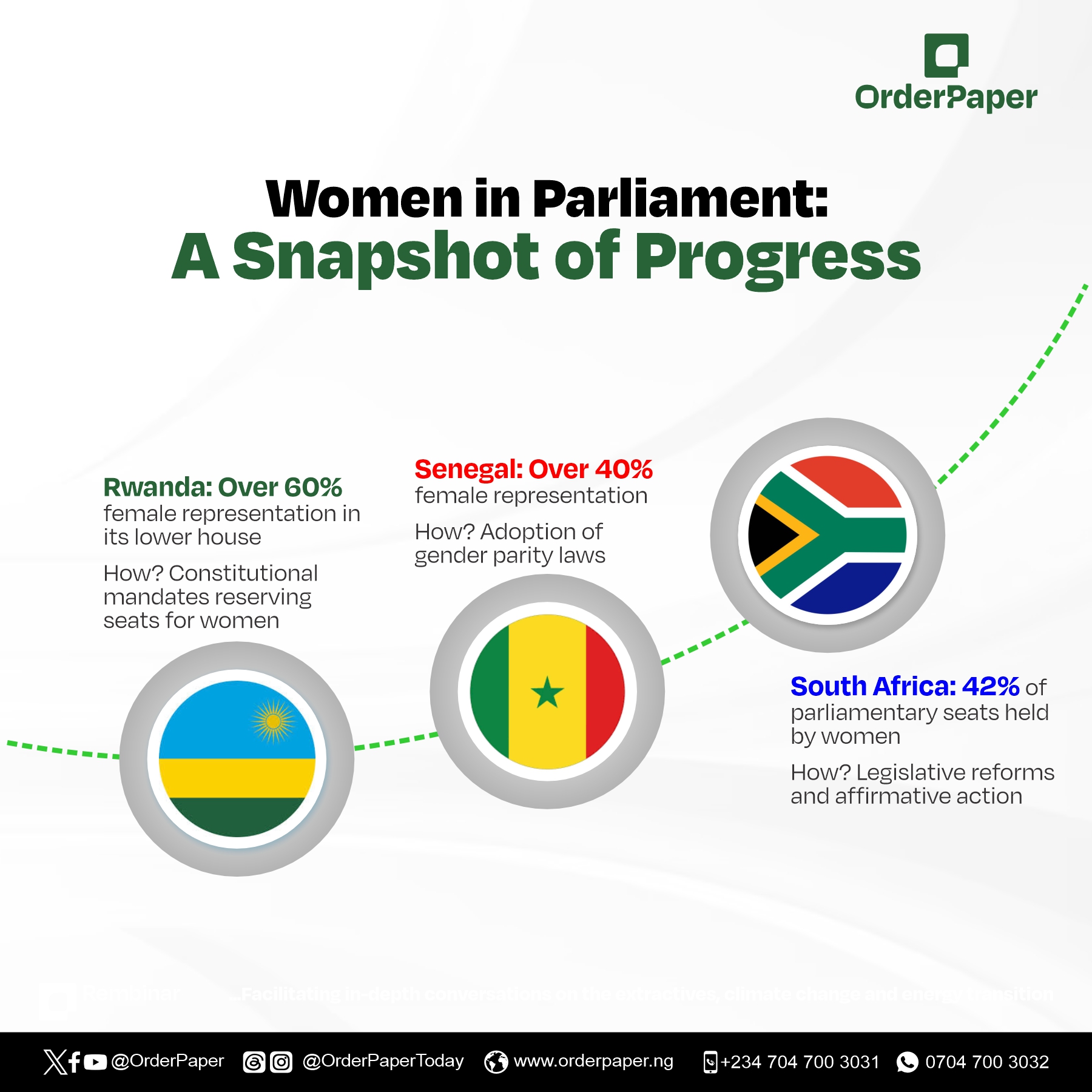

In stark contrast, countries like Rwanda and Senegal have implemented measures leading to substantial female representation in their parliaments. Rwanda, for instance, has achieved over 60 percent female representation in its lower house, largely due to constitutional mandates reserving seats for women. Similarly, Senegal has seen women’s representation surge to over 40 percent following the adoption of gender parity laws.

Also, South Africa has 42 percent of seats in parliament going to women. These examples underscore the effectiveness of legislative reforms and affirmative action in promoting gender-inclusive governance.

Can Nigeria Achieve Gender Parity?

Achieving gender parity in Nigeria’s political landscape remains a formidable challenge due to deep-rooted cultural, economic, and institutional barriers. While some progress has been made, overcoming these obstacles requires a collective effort from all sectors of society, including political parties and civil society organizations. Experiences from other African nations demonstrate that transformative change is possible through proactive policies, robust legal frameworks, and a strong societal commitment to inclusivity and representation.

However, legislative efforts to enhance women’s political participation continue to face resistance. During the second reading of the bill, lawmakers such as Rep Ghali Tijani (NNPP, Kano), Rep Olamijuwonlo Alao-Akala (APC, Oyo), Rep Billy Osawaru (APC, Edo), and Rep Patrick Umoh (APC, Akwa Ibom) opposed the bill, arguing that it was undemocratic and discriminatory against men. They insisted that political candidacy should be based solely on merit rather than gender and suggested that women should mobilize support for female candidates at the polls. While this argument might seem valid in an ideal democratic system, it overlooks the structural inequalities that prevent women from emerging as candidates in the first place.

The Economic and Social Case for Gender Inclusion

The benefits of gender-inclusive governance extend beyond representation. Research has shown that closing the gender gap in political and economic spheres can lead to significant national gains. Rep Kalu pointed out that increasing women’s representation in Nigeria could boost the country’s GDP by 9 percent by the end of 2025.

Furthermore, countries with higher female political participation have demonstrated improved healthcare outcomes, better education policies, and stronger social justice frameworks. As Rep Kalu rightly stated, “When women lead, communities thrive.” The inclusion of women in decision-making bodies ensures that critical social issues—such as maternal health, child education, and gender-based violence—receive the necessary legislative attention.

While Nigeria’s current statistics on women’s representation in parliament are concerning, the experiences of other African countries offer a roadmap for improvement. Embracing legislative reforms like the reserved seats for women bill could serve as a catalyst for change, fostering a more equitable and prosperous society.

The Natasha-Akpabio

Women in Nigerian politics face systemic barriers, including personal attacks, and perceived character assassination designed to undermine their integrity. The case involving Sen. Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan (PDP, Kogi) is seen by many as part of a broader pattern where women in leadership encounter coordinated attempts to discredit them, reinforcing stereotypes that question their legitimacy in governance.

Sen Natasha has sued Senate President Godswill Akpabio (APC, Akwa Ibom) to the tune of N100.3 billion for defamation. The suit follows a confrontation over senate sitting arrangements, which later escalated by alleged defamatory remarks from the Senate President’s aide Patrick Mfon on his Facebook page stating “Is the Local Content Committee of the Senate Natasha’s Birthright?” he further claimed that she had little understanding of legislative rules and suggested that she believed being a lawmaker was solely about “pancaking her face and wearing transparent outfits to the chambers.” This case highlights the intersection of gender, political power, and social inclusion in governance.

This is not the first case of female senators facing public intimidation. For instance, in the 8th Assembly, Senator Dino Melaye reportedly threatened to beat up Senator Remi Tinubu during a heated exchange in a closed-door session of the senate. This demonstrates how female lawmakers face hostility within the National Assembly.

READ ALSO: Natasha Slams Akpabio with N1.3 billion Lawsuit

Implications for Women’s Political Participation

This case underscores the broader GESI challenges in Nigerian politics. Structural power imbalances continue to disadvantage women, limiting their ability to operate freely in legislative spaces. Addressing these challenges requires:

- Stronger legislative protections against political defamation and harassment.

- Institutional reforms to combat gender bias in governance.

- Increased public awareness to challenge harmful narratives against women in leadership.

- Support networks to empower female lawmakers against political and social pressures.

Sen. Natasha’s lawsuit is more than a legal battle; it is a pivotal moment in addressing gendered power dynamics in Nigerian politics. We need to reinforce accountability for political actors and push for institutional reforms that ensure fairness, respect, and inclusivity for all lawmakers.

As Nigeria works toward a more representative democracy, prioritizing the visibility, respect, and protection of women in political spaces is essential.