The way and manner the senate handled the president’s state of emergency declaration echoes widespread concerns of a rubber stamp parliament

The historic approval of a state of emergency in Rivers state witnessed high-stakes drama that tested Nigeria’s democracy, the rule of law, and the very fabric of legislative independence. Just as the dust from Sen. Natasha’s case began to settle, the senate faced an even bigger storm, the escalating political turmoil in Rivers state.

For months, Rivers had been engulfed in a political battle between Governor Siminalayi Fubara and his predecessor, Nyesom Wike, now Minister of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Allegations of political sabotage spiralled into factional legislative sittings, high-stakes judicial decisions, and ultimate control over the treasury, leading to negative impacts on governance for almost two years.

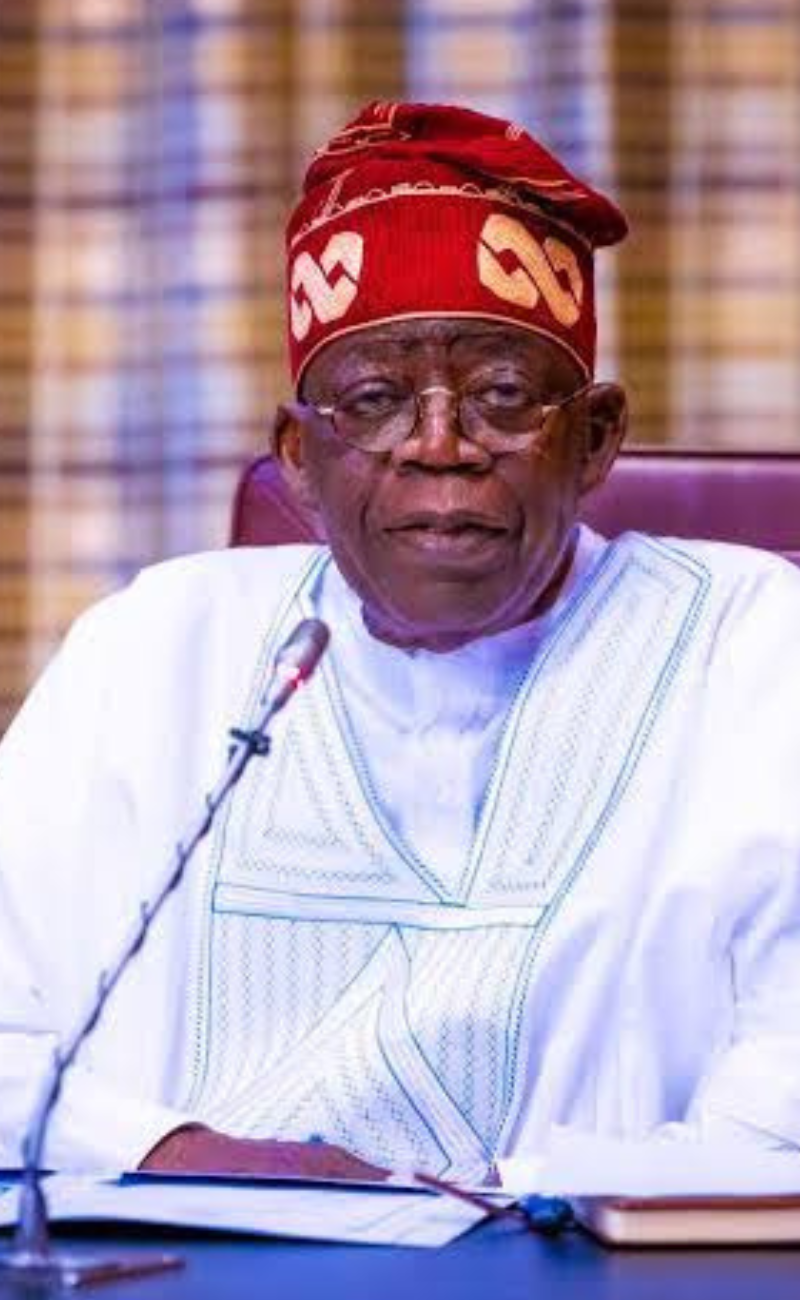

On March 18, President Bola Tinubu declared a state of emergency in the state, citing a breakdown of law and order, threats to national assets like oil pipelines, and the failure of local authorities to resolve the crisis. Tinubu also suspended Governor Fubara, Deputy Governor Ngozi Odu, and the entire Rivers House of Assembly for six months, appointing retired Vice Admiral Ibok-Ete Ibas as the sole administrator.

Constitutional requirement: Why senate’s role was crucial

It is important to note that when the president declares a state of emergency in any part of Nigeria, be it a state, region, or the entire country, the declaration does not stand solely on the president’s word. Section 305 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended) mandates that the National Assembly (Senate and House of Representatives) must approve the president’s proclamation within a specific timeframe:

“A proclamation issued by the President under this section shall cease to have effect—

(a) if it is revoked by the President; or

(b) if, within two days when the National Assembly is in session or, where the National Assembly is not then in session, within ten days after it next sits, the National Assembly does not pass a resolution approving the proclamation.”

Failure to meet this constitutional requirement automatically renders the proclamation invalid, meaning the state of emergency ends immediately.

Why the delay? Unspoken pressures behind the senate’s slow start

Interestingly, despite the gravity of the proclamation, the senate did not consider the emergency declaration immediately. Instead, the debate and vote took place the next day, March 20.

Insiders revealed that there was palpable tension within the senate on the first day. Lawmakers from the south-south, especially those loyal to Governor Siminalayi Fubara, allegedly held secret consultations, weighing the political risks of supporting the proclamation. Many feared backlash from their constituents, who saw the suspension of an elected governor as an assault on federalism.

The delay was thus less about legislative procedure and more a calculated pause and time needed for lawmakers to reconcile their allegiance to the president with the rage simmering in their constituencies.

There were also strong indications that the presidency lobbied intensely overnight, convincing reluctant lawmakers. The Rivers crisis, given its economic significance as Nigeria’s oil hub, placed the senate in a dilemma: align with their constituents and overwhelming public mood or please the executive to safeguard political survival. By the next day, a clearer path had been paved, pressure from the executive and fear of political isolation forced many senators to fall in line.

Senate debate turns chaotic: Akpabio-Dickson face-off

When the debate finally commenced, it was anything but smooth. Senate Leader Opeyemi Bamidele sought to reorder the day’s agenda to prioritise emergency debate. However, Sen. Seriake Dickson (PDP, Bayelsa west) raised a constitutional point of order, insisting the senate must first enter a closed session for sober reflection.

What followed was an explosive confrontation between Dickson and Senate President Godswill Akpabio who accused the former of granting television interviews opposing the emergency rule. He went further, ordering Dickson’s microphone switched off, a rare move that highlighted deepening fractures in the chamber. Dickson, visibly angered, reminded the chamber of the need for mutual respect, particularly from the presiding officer.

Closed-door session: Shielding the senators from their people?

Following the heated face-off, the senate retreated into a closed session that lasted over an hour. When they emerged, Akpabio announced that the senate, invoking Section 305 of the 1999 Constitution, had approved the state of emergency but with conditions:

1. The emergency must not exceed six months and can be reviewed or terminated by the President.

2. A joint administrative committee of both chambers will oversee governance in Rivers State.

3. A Committee of eminent Nigerians will attempt reconciliation between warring factions.

But why the secrecy of a closed-door session? Was it a tactical move? Facing nationwide scrutiny and internal dissent, senators needed a safe space to align with executive demands without public accountability. Voting openly risked exposure to political backlash.

Or was the closed-door session an avenue to trade deals, promises of re-election support, contracts, or political survival in exchange for complicity? Either way, the senate’s decision to shield its deliberations from Nigerians reinforced public fears of a senate more loyal to President Tinubu than the people.

A voice vote – After billions spent on technology and exotic cars

As shocking as the closed-door session was, the senate’s decision to adopt a voice vote rather than electronic voting added insult to injury. Despite billions spent renovating the National Assembly complex, funds that covered state-of-the-art chambers, electronic voting systems, and luxury SUVs for lawmakers, the senate claimed the machines were “not functional.”

Instead, the decision that suspended an elected governor and disbanded a state assembly was made by voice vote, an archaic, opaque method vulnerable to manipulation. For many Nigerians, this was no accident but a deliberate ploy to erase individual accountability. A digital footprint of votes could have haunted senators at election time. The voice vote gave them plausible deniability, leaving Nigerians unable to trace who voted for or against the controversial measure.

Echoes of the Ahmad Lawan era: Senate as executive appendage?

The questionable approval of the emergency rule rekindled memories of the Ahmad Lawan-led senate infamously branded a “rubber stamp” of the executive. Lawan’s tenure saw the National Assembly nodding through nearly every executive request, raising fears about the collapse of checks and balances.

Akpabio’s senate now faces similar accusations. Rather than defend democratic principles, the red chamber seemed focused on protecting the President’s interests even at the cost of the Constitution. The ease with which the senate sacrificed federalism by approving the suspension of elected officials signals that Nigeria’s legislature may have fully morphed into an appendage of the presidency.

Seriake Dickson: A lone voice in the wilderness

Among the 109 senators, only Seriake Dickson stood his ground, maybe or not for the show. A former governor and seasoned lawmaker, Dickson challenged Akpabio openly, risking political fallout to uphold procedural fairness.

But where was the rest of the opposition? The silence of other PDP senators and minority party lawmakers was deafening. Maybe the senators feared reprisals, while others had quietly cut deals to remain in the presidency’s good graces ahead of future elections.

Dickson’s lone stand laid bare the senate’s moral crisis: loyalty to power now trumps loyalty to the people or the Constitution.

The overlooked human cost: Democracy’s casualties in Rivers State

Amid this power play, the real victims remain the ordinary citizens of Rivers State. With elected officials suspended and governance now militarised under an unelected administrator, Rivers State’s residents face a bleak future. Public services have stalled, the economy suffers, and violence simmers.

Yet, in Abuja, lawmakers prioritised personal political survival over the people’s welfare. The Rivers crisis is no longer just a local issue, it is a symbol of Nigeria’s democratic decay.

For the first time since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, the senate approved a full state of emergency that suspended elected officials. It is a dangerous precedent, suggesting that political disagreements, especially those involving resource-rich states can now be resolved through executive fiat rather than constitutional means.

The question now is simple: Will the senate ever rediscover its courage and independence? Or has Nigeria entered an era where legislators exist merely to endorse the President’s will? Time, as always, will tell.